Designing a Programming Language: I

Designing a language and building an interpreter from beginning to end.

Part 1: The Premise

Programming languages come in a variety of different paradigms. Even so, there tend to be two main camps along the language front. There are static languages and there are dynamic languages. To avoid too much history and any sort of in-depth analysis, this article will simplify things with a number of assumptions. One assumption we will make which might not always hold true is that programs written in static languages are compiled to machine code, while programs that are written in dynamic languages run in an interpreter.

Testing the definitions of what makes a language static or dynamic might illustrate this more. In a static language, variables and procedures have rigidly defined types. Attempting to access a value that has not been named in a relevant scope leads to a syntax error issued at compile time. The programming language is organized in such a way that, when it is analyzed at a source level, the locations of all variables and functions are known by lexical address: i.e. given the relevant scope, a variable can be identified by the order it is defined in.

As an example, consider the case of declaring variables in Java:

int num1, num2;

String text;

This would be the prototype for a static language. When variables are first declared, they must be paired with a type. In order to compare with a dynamically typed language, let's look at an example from Python.

global num1, num2

global text

In this example, no types are declared for these variables. The variable 'num1' could be used as any type by assigning any value to it. Additionally, the declaration step is wholly unnecessary. The way that values are stored includes type information, so declarations are only needed when declaring scope.

Additional examples of dynamically typed languages besides Python include JavaScript, Ruby, Lua, Clojure, Scheme and Lisp, and a number of others. Aside from the style of syntax and the degree of expressiveness, these programming languages are largely similar because of their type system. So called dynamically typed languages are sometimes referred to as duck-typed or duck languages.

Adopting many of these identifying features, and really as an exercise in constructing a language from basic parts, we will build the Duck programming language from the ground up. We will explore this process without regard to its pragmatism or practicality. Indeed, any ideas of utility will come only after we have completed the process.

As a fair warning, I feel I should mention that the upcoming sections may contain some complex material, even though it is presented plainly and simply wherever it can be. For that reason, I would recommend the reader do some research on the topic of programming language design before embarking on this journey. With that said, we are on our way.

Part 2: The Syntax

At this point it might be easy to scrabble together a document of syntactic expressions, beginner how-to tutorials, Wikis, or grammar guides as an explanation of the language and drop the topic altogether, moving on to more productive tasks. Sometimes it seems like the design of a language, down to its true grammar, is something more for liner-notes on a reference manual than something that exists that has been written, crafted, or changed over time. The purpose of this explanation is not to suggest that your programming language should be chiselled into stone and that that is how great concepts come to fruition. Instead, true to the nature of our task, we will at every step of the way look at how things can be changed, expanded, and made to evolve over time. What might be suitable for one task is not the solution to every problem, and having a way to change things or reuse our efforts is always good.

With that in mind, we will sort of gloss over what the fundamental mechanics of the Duck language are at the atomic level. Instead, we will explore what the essence is. We want to discover the intention of the language itself. If we can get into the mind, the feng-shui, or the essential attitudes of the programming language, that would be enough. Still, programming languages are systems that we use to express ideas. And for any manner of communication to be useful, we need to have some common ground.

We will create a language that is very neutral to the background of the programmer. We will also work in an imperative style. Although certain ideas of functional nature may seep through eventually, we are trying to build the basic language for the common programmer.

To find a root concept we can work from, let's begin with statements. There are statements that form operations. Given two values, add them together and assign the result. If an expression is true, execute a block of statements. Evaluate expressions and then make a procedure call with arguments. Etcetera. A block of statements will be described in terms of a statement list. Given a function declaration, a kind of statement, there is a name for the function, a list of parameter names, and a list of statements making up the body. An If/Else statement has a similar nature. It is a statement that contains additional statements.

To provide a little bit of framework to work from, let's write down what some of these ideas might look like.

if some condition then

; here is a block of statements

end

This is what our basic if statement looks like. Considering that we will often want to execute statements if our condition is false, we better add support for else statements, too.

if some condition then

; here is a block of statements

; to run if the condition is true

else

; here is a block of statements

; to run if the condition is false

end

Looking at the syntax we have, we seem to have borrowed the end-block notation from Lua. I guess this is just coincidental. We could just as easily have styled our language after BASIC and terminated IF statements with ENDIF rather than simply the keyword end. I don't have any real justification for this.

What I would justify, however, is the use of real words in syntax. I think this is plainer and more easily readable or simpler to understand than using a large amount of syntactic symbols to delineate blocks and other control structures. So wherever we can, we will use whole words in our language's grammar.

As before we introduced the idea of a function definition, or a function declaration, let's jot down what that looks like.

function our_new_function(parameter1, parameters2)

; here we have statements that do work

; if this function returns a value then we might have

return ourResult

; at the end

end

We won't put any limitations on the placement of these. Functions can be defined inside of functions. In this case they will be local to where they are defined. We don't want to introduce limitations when forming our definitions from the start, because they might be based on expectations that aren't true. If the limitations we impose on ourselves are artificial, then we will be putting time and effort into enforcing artificial limitations, and that becomes wasted effort. On functions, the use of end as a keyword seems more justifiable, as it is much shorter than end function. A good middle-ground might be endf. This depends on if we want to allow END to be a specific command that terminates the running program. I always thought this might be a useful instruction, but it's not often included in languages. Instead, we might have a system command for quit() that we can invoke from our program.

Our language must have some common ground with existing languages, so we will use familiar constructs like for loops and while loops. For loops will use ranges in an explicit way. There will be a beginning value and ending value, and the loop body will be executed for both of these and every value in between. This is assuming we are starting with integers, or possibly floating-point numbers, but always increasing by increments of one.

Our for loop syntax.

for j = 1 to 100 do

; this prints the numbers 1 through 100

println(j)

loop

Our while loop syntax.

while running do

println("still running")

loop

We will allow all of the basic operations we have come to expect. Namely addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, as well as modulo division (something we could implement ourselves), string concatenation for convenience, negation, not, and Boolean expressions. These are the fundamentals.

We are trying to accomplish creating the most flexible and programmable language, so we must also think of distinctly dynamic elements that we can add. Arrays are fundamentally useful. Let's add arrays that allow the use of any index, without specifying a container size. Let's expand this array functionality to allow for values of any type to be used as indices. Furthermore, let's create dictionary types with a familiar object notation. These will be similar to classes or structs from related languages. To increase flexibility, these will be the same object internally as arrays, and the syntax for each can be used interchangeably.

arr1 = []

arr2 = [1, 2, 3, 4]

dict2 = {firstArray: arr1, secondArray: arr2}

dict1 = {"a": 1, "b": 2, "c": 3}

arr2[4] = 5

dict2.arr2[5] = 6

dict1.d = 4

Our array and dictionary example.

Another feature that increases our flexibility is allowing functions to be first-class objects. This means that we can use functions as parameters, return them as values, and assign them to named variables. We can rename a function and use the original name for something else. We can attach functions to objects and use them as classes. Although passing functions as first-class objects is a functional idea, here it overlaps with the ideas of dynamic languages so we will adopt this feature. In order to keep track of objects and complex types, it makes sense to implement memory management through garbage collection, instead of passing that large responsibility on to the programmer adapting to use our language.

Roughly this is a description of the language we intend to create.

Part 3: The Set Up

A casual reader following along might not be interested in developing their own language, as of this moment. They might be more interested in the mechanics involved. As a rather elaborate exercise, I invite anyone to attempt to create their own interpreted programming language. That being said, I am about to outline the process and tools that I used to create the Duck programming language, even though I recognize there are multiple ways to go about the process.

For example, I chose to write everything in the C programming language. This is really a more difficult task than it has to be, but I will explain my decision further on. It might be easier for a developer to go about creating a language with any other environment. A truly dedicated engineer might have already targeted a platform and decided to start from the get-go with handwritten assembly language. This is not a very portable solution. Another endeavoring developer might start with a modern language like Java or C#. These are great choices and I would encourage picking up whatever tools you are familiar with. For reasons that may or may not be obvious, I would recommend fashioning this dynamic language we are creating in a static host environment. So, a language like Go would be preferred to Scheme. I know that a number of courses teach programming languages by implementing a Scheme or Lisp interpreter. What we are doing is not far off from that except for large differences in style and syntax. And usually these courses require writing the language interpreter in the language itself, or involve a similar kind of task. The reason I would recommend staying away from this course is because it begins to lead to deliberately impractical solutions. The performance you can get from a self-hosted environment is really only half-way there, and any of the benefits of the solution we are creating tend to get taken away. Forging special frontends for a language can be very useful, and there are ways to improve productivity and performance by creating a special dialect, but what we are going for is an entirely new language.

I will note that there is one way that implementing this dynamic language in an interpreted or scripting language might be helpful, and that would be in the case of cross-compiling. I.e. having our Duck code reduced to some other language, like JavaScript or Python, before being executed. That would be fine but then we are dealing with code compiling and other complexities which are best addressed in section II of this series.

Reasons supporting my decision to use C are chiefly that:

It is portable. A program written in C can be deployed on virtually any operating system. It is easy to compile for any device and can be executed on almost any microprocessor. Especially when this code is written with the standards in mind. I would also choose to avoid any new features in the language to maximize compatibility.

It is low-level. Without delving into assembly and machine code itself, C represents a close barrier to the target machine itself. Not knowing what CPU our code will execute on or the exact layout of registers, we want to be aware of what sort of instructions will be executed and how our program will be laid out in memory.

It is not garbage collected. While this point can be debated, the purpose of this project is in ways to create something new. So, creating a new language with higher level features, it is easier to feel a sense of accomplishment when we are working on features we didn't have from the start. This also helps us to have control over the runtime for our final interpreter, as we are being dealt the responsibility of memory management ourselves.

It's difficult. This hardly qualifies as a reason. I would say that one reason would be 'because it is fast,' but knowing how the process of writing has gone, it is neither fast to implement nor necessarily the fastest resulting code. But true to form, this exercise will be a challenge, so it might as well be a good one.

Now this doesn't particularly qualify as a language concern, but as an additional challenge, the project is being built from the ground-up, in a pulled-up-by-its-own-bootstraps kind of way. That means, as you see the parts of development around the parser and lexer coming together, two fundamental components of a language, these will all be hand-fashioned parts and tools. The inner workings of the parser generator will be explained. This completely overlooks any debates that might be had about tools to use like Bison, Flex, Yacc, or Lex. A number of tools that I know very little about.

We are also working from our own frontend and our own backend. That means we aren't plugging into LLVM or tying in with Clang or anything like that. We are using an ANSI compiler with a CMake script.

If you yourself are developing something in parallel with this project or on your own, I would recommend using all of these great tools and resources, which would speed-up your journey significantly and you could be done with your project before you finish reading this guide.

Even considering our target platform and the technical specs we are about to jump through, there will be very little actual code provided or directly cited. There may be resources attached, but, in general things will be outlined from an algorithmic approach or described in pseudo-code. There is no reason to go about annotations on a line by line basis.

Part 4: The Lexer

The goal of the lexer is to take a target source file and create a stream of lexemes which we will call lexer tokens. Internally, we will represent these as a linked list of elements, each of which tracks an integer identifying what kind of token it is (symbol, keyword, or identifier as examples), the raw source string and its length, and the line number the token appears on in the source file.

Upon taking a source file as input, the lexer will create a new buffer and remove redundant whitespace, single line comments, and multi-line comments. Successive whitespace characters will be replaced with a single space, unless that stream includes a newline, in which case a newline will be used. This process is used to 'strip clean' the source file until we are dealing with program source directly. Now we will work character by character to isolate and identify the tokens that make up Duck source code.

At this point, we already have tables of keywords and symbols to begin with, and if we don't, it is something that we will generate in one of the next steps that we can save and store for use in the lexer. In any case, we can list off all of the keywords and symbols that we would like to use for our programming language. In this case those keywords are:

import, include, return, break, continue, throw, function, end, if, then, else, for, to, do, loop, step, in, while, let, begin, try, complete, catch, object, static, operator, this, and, or, not, is, mod, new, true, false

Some of these include keywords for features we haven't discussed implementing. This is fine, we can use them as reserved words while we contemplate the additions we can make to the language down the road.

Our lexer will begin by looking at the next input character. Here at the start, we will look at the first non-commented out character in our source file's source text. It may be a letter, a number, another type of glyph like parentheses or a plus-sign, a whitespace character, or a newline character. If it is a whitespace character we can ignore it. At this point, we are only using whitespace as a delimiter. It marks a boundary between tokens that must be separated, like keywords and identifier names. Not all tokens will be divided by whitespace, as it is possible for certain characters to follow each other that form different tokens.

Let's assume that we encounter a character from the alphabet. Then we could be looking at an identifier (something we use in the program to label a variable, procedure, or field) or a keyword. Following the conventions for naming identifiers in our language, we will allow anything that starts with a letter and continues with any combination of letters, numbers, or underscores to name a variable. So we will continue scanning until we reach a character that does not match or until we reach the end of the input; At this point we will either add an identifier or a keyword to our list of lexemes. We will have to check our list of keywords to see if this identifier is in fact a keyword. In that case, our lexer emits a 'token' instead and finds the right token constant for this keyword, here its index in our list. Otherwise, we add an identifier token to the lexemes and attach the string literal for the identifier.

If we encounter a number, we will continue while we see numbers or decimal points until we see another character or reach the end of the input. If this sequence contains a decimal point, then we will assume this is a real number or a floating-point constant. Otherwise, we will interpret this number as an integer. We add a token for either an integer or a float to our lexer tokens and include the literal string for the sequence to use when we need access to that value.

If we hit a symbol glyph, which we will use to unambiguously refer to characters that are not alphanumeric, whitespace, or newlines, then we will find the longest sequence of glyphs that correctly match a preset collection of tokens and add that token to our list of tokens. When I talk about a preset collection of tokens, I refer to the following set, which we will be generating soon in the next step.

These built-in token symbols used in our programming language are:

, = ( ) [ ] + - * / . == != < > <= >= ! { } :

Noticing that we notably missed quotation marks, we must go back and add strings to the collection of objects that we lex, mainly because we do not want to be lexing what's on the inside of quoted strings, and we certainly don't want to be parsing them, either. So if we encounter a glyph that is a string, or specifically if we encounter a character that is an opening quotation mark, so either a single or double-quote, then we must scan the input until we find the matching end quotation. We'll then add this to our list of lexemes as a string token, and include the quoted text as the literal string.

Then, if we encounter a newline, we will emit a newline token, as our language will use these to aid in its grammatical structure. After we have lexed any one token or lexeme, we advance the input to the end of that token and continue lexing the source text, until we have reached the end of our input. At the end of the program, we add another token which represents the end of file. In literal form we'll denote this as <$>, even though there is no time we will be writing this within our program itself, just in providing documentation and analysis.

What we now have is a complete list of tokens that represents the entire workable source code of the program. We can discard any extraneous data structures that we are using at this point, close any file handles, and free any temporary buffers. Our token stream will then be passed on to our parser to generate an abstract syntax tree.

Part 5: The Parser

We cannot yet talk about the parser until we talk about parser generators. Here I should mention that in our quest to find the most flexible way of going about doing things, we may be taking some extra-steps. As I said before, an enterprising programmer might start from the outset programming in assembly. While we have made our choices not to go that route, we have to look at the other more direct paths that we are giving up. This is in some ways a domain specific language that we are constructing. If we were really in-tune with what we wanted our resulting programming language to look like and how it should behave, we might be able to wrap the parsing and lexing steps all in to one. Or in any case, we could forego generating a parser and start writing one by hand.

This would be in lieu of formalizing the language's grammar. Instead, we would create our own specially crafted loop that would process each kind of statement, and in-turn would match up symbols. This describes what might be called a "recursive descent parser" and it is one form of top-down parsing.

Unfortunately, top down parsers have their limitations. Without getting too pedantic, we will simply say that our recursive descent parser would be limited by its complexity in writing, the set of language structures it could parse, and possibly its runtime efficiency. As a counterpoint, it might be very flexible to minor changes in the language. I would also like to note that, as one method of by-hand parsing, the top-down recursive descent parser lies close to an area of do-it-yourself parsing techniques that might very well be able to parse any grammar. From a computational theory perspective, a function can be written in any sufficiently suitable language to recognize any deterministic language. But we are looking for a more sure-footed answer than that.

There are a class of languages known as context-free languages which we will focus on. Context-free languages are the class of languages that can be recognized or generated by a context-free grammar. This applies to us as we will most likely be writing our programming language as a context-free language, or something close it. In any case, we will be combining the power of our lexer, our parser, and any processing we might do before or after parsing to form our programming language. At this point we need to concern ourselves with context-free languages and to what extent they apply, so we will take a brief overview of what LR(k) languages are, what LR(1) languages are, and how we can use the LR algorithm to write a generic parser for any sort of grammar we can think of. We will be working with context-free grammars and we will need to come up with our own notation. For this we will use BNF form because it is easily understood.

What we are describing is a bottom-up parser that works from left to right and produces a rightmost derivation. The parser takes our input stream of tokens and it creates an abstract syntax tree, a tree of related productions, based on a set of rules that we provide it describing how productions are formed. It is a shift-reduce parser, meaning it operates on one token at a time, while using a stack, to either shift a token or reduce a production.

In order to do this, the parser needs a large table to guide it in its operations. This table will be based on the rules to our production grammar and it will outline a finite number of states that the parser can exist in while it is in the process of parsing.

Context-Free Grammars

Let us first look at an example from our grammar.

<expr> ::= <expr> + <term>

<term> ::= <term> * <factor>

<expr> ::= <term>

<term> ::= <factor>

<factor> ::= <integer>

We will call this the arithmetic grammar. It describes the way expressions can be constructed out of addition and multiplication operations.

To aid in our understanding, we will also start looking at another formal grammar, the balanced parentheses language, which is also a subset of our programming language's final context-free grammar.

<S> ::= ( <S> )

<S> ::= <S> <S>

<S> ::= <epsilon>

Now this might not be immediately obvious, but from these first two examples we have already introduced a few basic notions about what our formalized grammars will look like, and as we begin to operate on them with machine programs, how we will be formally operating on them. Our grammar is formed with a set of rules that we will call productions, ordered by the line number they appear on. Implicitly, we will have a rule introduced when we load this grammar from file that says the program root reduces to the first non-terminal symbol we see, which is the left-hand side of the first production. In example 1 above, this is the <expr> symbol. In the balanced parentheses language, example 2, that is the <S> symbol.

This leads to the next major concept. Our grammar is formed by terminal and non-terminal symbols/tokens. The plus '+' sign in the first example is a token. Therefore it is a terminal. There is no way that the plus sign will expand into more symbols or tokens in our program. It itself is a terminal production.

Non-terminals are symbols that we defined in the grammar itself. <expr>, <term> and <factor> are all non-terminal symbols. <S> is also a non-terminal. As we have formed rules with left and right-hand sides, divided by the ::= operator, we've noticed that symbols are delimited by angle braces. And we've already accounted for the tokens that we recognize as being terminal symbols. So what about the other symbols? <integer> is a built in terminal. It is synonymous with the lexer token produced by integers in the lexing phase. Similarly, <epsilon> is a built in terminal. It is something that we are defining inside of the parser. But what does it represent? It is synonymous with an empty production. In the case of the second example, it is the production we reach when we run out of parentheses.

Other examples of built-in symbols that we might need and need to use are <endl> for newlines in the source, <string> which we would use for string literals, <float> for floating-point numbers our lexer identifies, and <identifier> which would match identifiers we find, or named variables. We can define Boolean types ourselves as a symbol that reduces to true or false, which would then become keywords.

Our parser generator will load a context-free grammar as a ".cfg" file and will itself parse the production rules from this file. For convenience, we will allow for comments in the grammar as lines starting with a ';' semicolon. Then we begin by working line-by-line. If this line isn't blank or beginning with a comment, then it is a new rule. First, we must identify the left-hand side. We will work by finding the beginning and end brace '<' and '>'. We are using newlines for a special purpose in enumerating rules, so these cannot occur anywhere in the left or right-hand side of the production, however use of spaces and other symbols is permissible, as long as everywhere the non-terminal symbol occurs, it is used with the exact same matching literal. Once we've identified the left hand side, we will generate a symbol identifier for it. This is a unique number that corresponds to this symbol. We will be building a table of symbols as we go, so if we encounter the same symbol again, we will use the same integer value. After identifying the left-hand side, we will look for the BNF symbol that divides the production.

In parsing the right hand side of a production rule, we will look for either another symbol, identified with angle braces, or a keyword/token. In the case that we need less-than or greater-than symbols to appear in our production rules, we will use a backslash to delimit them, such as "\<". On finding whitespace, we will just advance to finding the next token, but if we encounter any symbol other than the beginning of a non-terminal symbol's token, then we will use this as a terminal and add it to our list of tokens for the lexer. Encountering a keyword, this will be added to the list of tokens and its token number will be added to the rule. So eventually we have rules that are determined by a left-hand side (LHS) non-terminal symbol and a right-hand side (RHS) of terminal and non-terminal symbols, all of which are determined by identifying integer constants. We also have a table of keywords and symbol glyphs that we can provide to the lexer.

Building LR(1) Parse Tables

Let's revisit the ideas of LR(k) and LR(1) grammars. An LR(k) grammar is a grammar for which an LR(k) parser can successfully generate a parse tree when given k tokens of lookahead. An LR(1) grammar is a grammar for which an LR(1) parser can successfully generate a parse tree when given one token lookahead. The set of LR(k) languages contains the set of all deterministic, context-free languages. Interestingly enough, the set of LR(1) languages contains the set of LR(k) languages, meaning that any LR(k) grammar can be recognized by an LR(1) parser if it is rewritten as an LR(1) grammar. This is convenient because trying to deal with an excessive number of lookahead tokens, either when building parse tables or when parsing, could become very bothersome. In terms of forming our grammar it means that each of our production rules should be able to be differentiated from the others by using a single lookahead token. In summation, we need to make unambiguous grammars.

The process of building a parse table from the grammar is slightly more complex. In a pseudo-overview of the algorithm, the process is as follows. First, nullable non-terminals must be identified. These are any of the cases where a non-terminal symbol may reduce to an <epsilon> production. In the above example, example 2, this is seen with the <S> token. Indeed, an empty stream of lexing tokens would be recognized by this parser. This is also a transitive property. If a non-terminal symbol reduces to another non-terminal symbol which is nullable, then it itself is a nullable non-terminal. Additionally, if a non-terminal symbol reduces to a production with any number of nullable non-terminal symbols, without any terminals, then it is a nullable non-terminal. These symbols are all identified first in a table.

Next, a table of first sets is generated. Given any non-terminal symbol or left-hand production symbol, the first set FIRST(a) represents the possible terminal tokens that may appear as the first token in any given production. This is built as a set by looking through all the possible productions that may be taken, taking into consideration which productions are nullable.

Next, a table of follow sets is generated, using the first set and set of nullable non-terminals as references. The follow set or FOLLOW(a) represents the possible terminal tokens that may appear after a production. The LR(1) algorithm uses a look-a-head of one symbol when parsing, so this helps the parser determine which state to transition to next. In the case of the root or base production, the follow set will include <$>. For other productions, it will include the set of terminals that may come after that production in any context it might be found in this given grammar.

First Set Examples

We have already determined the nullable non-terminals fairly easily. In practice, a larger context-free grammar may be complex enough that it would take a fair bit more work. In any case, I'm relatively certain that we can implement this logic in code.

To help in understanding the concept of the FIRST(a) set, I will give examples for each of the (small) sample grammars.

An example from the arithmetic language.

| Symbol | First Set |

|---|---|

| <expr> | integer |

| <term> | integer |

| <factor> | integer |

Here we see that, each of these productions must begin with an integer token.

Now consider the parentheses language.

| Symbol | First Set |

|---|---|

| <S> | ( |

This one is even simpler. The only token that begins the <S> symbol's production in our grammar is the open parentheses symbol. In the case that it is empty, I suppose the first token might be <epsilon> but this is information we already have from the nullable non-terminals set, and we generally won't consider <epsilon> as a terminal token.

Follow Set Examples

Now for examples from the follow set. These sets require the FIRST set to generate, but they also must consider other tokens in a production rule. Building these sets involves looking at each production rule and seeing what tokens follow any possible symbols. In addition, the process is only complete when all possibilities have been considered. Since each symbol could be dependent on another symbol's FIRST and FOLLOW sets, the algorithm really must be ran repeatedly until there are no more changes to the FOLLOW set.

Here, let's look at the arithmetic language.

| Symbol | Follow Set |

|---|---|

| <expr> | +, <$> |

| <term> | *, +, <$> |

| <factor> | *, +, <$> |

In this case, we've added the end of file token. That's because any of these symbols can be the last symbol in our language. The only thing following that is our end of input. An expression can be followed by a '+' plus sign, we can identify that from our first rule. There's nothing else that can follow it because no other rule uses the <expr> symbol on the right-hand side (aside from our implicit rule, <start> ::= <expr> <$>). Next we look at the <term> symbol. In rule #2, <term> is followed by a '*' multiplication sign. Rule #3 says a <term> can be used anywhere an <expr> is, so <term>'s follow set must include <expr>'s follow set as a sub-set. The same goes for our <factor> symbol.

Now let's look at the balanced parentheses language.

| Symbol | Follow Set |

|---|---|

| <S> | (, ), <$> |

It's clear from rule #1 that ')' should be in the follow set. It follows <S> right? And it's also clear from rules #0 and #1 that <$> would be in the follow set again. But where does the '(' opening parentheses symbol come from? Consider rule #2 where <S> ::= <S> <S>. As <S> follows <S>, all of the elements from the First set for <S> must be in the Follow set for <S>. So we add that opening parentheses sign.

Note: things can get more complex when we have nullable non-terminal symbols sandwiched in the middle of a grammar rule. For a moment consider this imaginary rule <A> ::= <A> <B> <C>. When building <A>'s Follow set, of course we would start with the First set from <B>. But in the case that <B> can be null, we must remember to include the First set of <C>. To give an even more complex example, consider the imaginary rule <D> ::= <A> <B> <C>. Again we are trying to determine <A>'s Follow set. We would do the same as above, but now what if <C> is a nullable non-terminal as well? Then <A>'s Follow set must contain all of the elements of <D>'s Follow set. (The first imaginary rule is insufficient for this example as saying <A>'s Follow set must contain the elements of <A>'s Follow set really tells us nothing.)

The Canonical Collection of LR(1) Item Sets

With these sets generated, the canonical collection is the penultimate set to be constructed. Using a pair of operations known as the Goto set and the Closure of a set, the canonical collection is formed by repeatedly adding LR items to a collection and using these item sets to form new item sets, until nothing more can be added to the collection. Each item set in the canonical collection represents one enumerated state in the final parser.

Finally, the parse table itself is constructed using the canonical collection and our original grammar rules. Using the Goto sets of each item set from the canonical collection, and the lookahead token from each item in the item set, a table of shift and reduce actions is built. This yields a Goto table and an Action table, the former of which determines state transitions from one parser state to another given a non-terminal symbol, and the latter of which determines shift, reduce, or accept actions for the parser given the state and terminal symbol on top from the program input. The accept action indicates that the parsing operation is complete. If the parser fails to create a matching syntax tree from the source because it does not recognize the language, then a number of different errors may occur which prevent the source from being accepted.

The actual code for building the LR(1) parse tables is as follows:

int BuildLRParser(GRAMMAR_TABLE grammar,

LR_TABLE* parser)

{

LR_ITEM_COLLECTION* C;

FindNullableNonterminals(&grammar);

BuildFirstSets(&grammar);

BuildFollowSets(&grammar);

// building the collection of item sets for an LR(1) grammar

C = CanonicalCollection(&grammar);

RemoveEpsilons(&grammar);

*parser = ConstructTable(C, &grammar);

FreeCollection(C);

return 0;

}Again, this process starts with rules and building the First and Follow sets after finding nullable non-terminal symbols. Then the canonical collection is formed by taking LR items, which are productions paired with a parsing position. We write this as a dot in the middle of the production. This information is combined with a lookahead symbol, which provides information about the next expected input. Starting from beginning of the root production with an end of file lookahead, the canonical collection builds an LR item set. The algorithm repeatedly advances the token and finds the closure of these items to expand the set. There are other sets that do not fit inside the closure of this item set, so the canonical collection is a collection built from these sets.

As was said before, there are a number of ready made solutions for parser generators out there that have already been developed and tested. Many of them use LALR or SLR algorithms, which we will find are slightly less generalized and less powerful than the LR(1) algorithm, but generally more compact in the tables they generate. The custom made parser generator that we have designed has been split from the Duck programming language project into its own repository, available here, for those looking for the original source code.

Stack-based Parsing

The parser itself starts from state zero and works from the token stream yielded by the lexer to provide input to the LR(1) algorithm. Actions are pulled from the action table based on this input token and the parsers state. If a reduce action is encountered, then given the size of the corresponding production, that many symbols and states are popped from the stack and added to a tree leaf. This tree is then pushed onto the stack as well as the next state from the Goto table. Successive states are taken from the top of the stack to determine the parser's next move.

If a shift action is encountered, the input token is pushed to the stack followed by the shift value, which represents a parser state. Our parser has a special step in the reduce case that identifies if the left-hand side is the goal symbol. In this case, it identifies the tree leaf to be the program's root element and stores it.

Finally, when the accept action is reached, the parsing is complete. If another state is encountered, the stack is empty, or another unhandled error occurs, we can say that the parse failed and provide the input token that it failed on. Since we have line numbers for tokens, we can indicate which line the parsing failed on. And given a bit more knowledge of the parser, we can identify whether there was an error due to running out of input, because of a specific syntax error, or other special cases. And given the specific failed token/production we could easily provide customized error messages that indicate what was wrong with the input source. These are all ancillary needs.

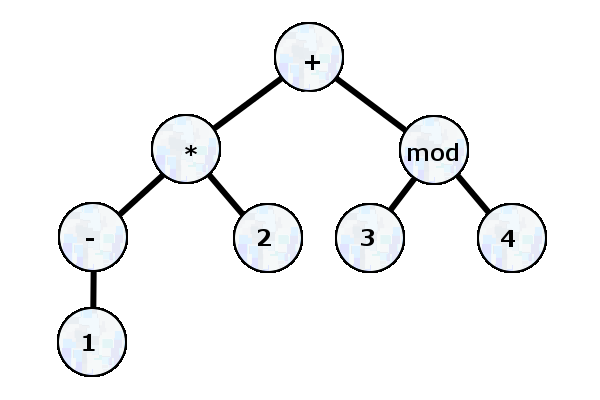

As an example of what our resulting syntax tree will look like, let's look again at a simplified example. The grammar for our language deals with a number of different language constructs. We have if's/else's, functions, while loops, and for loops. Each of these statements must have some type of code to run, so we also must have assignment statements. Our loops and conditionals need conditions to evaluate, so we also require Boolean expressions. This necessitates a whole framework of expressions.

To support all the operations of math that we require, as well as logic, function composition, variable and array referencing, we will need to create a grammar for expressions. Including that entire description here might be excessive, so let's consider again just arithmetic and algebraic expressions. Let's assume that we have our operations set up for addition, multiplication, and modulus division as we mentioned before. Looking at our first example grammar, we can see how we might set up a hierarchy for orders of operations. In addition, we'll add parentheses as another requirement to maintain operator precedence.

Given all of these structures, we may make way to parsing this given expression:

-1 * 2 + 3 mod 4

As we declined to include negative numbers in the definition of our lexer, we'll also have to add negation to one of the operators in our programming language. After this sequence has passed through the lexer, it will be given to the parser. The parser will recognize it as a statement that simply reads as a standalone expression. The expression is made up of terms and factors and then generates an abstract syntax tree. Initially, this tree will contain a number of branches that connect nodes in trivial ways. As we said before, sometimes an expression is just a term, and sometimes a term is just a factor. To avoid operating on trivial constructions, or at least for viewing what this syntax tree looks like, we will want to eliminate trivially simple productions. This is easily handled by making a list of all of the trivial productions. Then let's view what the syntax tree for this statement looks like.

With the abstract syntax tree in hand, a tree of productions that enumerate children, each of which at a root-level consist of tree nodes or lexer-token terminals, we are left to interpret the abstract syntax of our programming language's programs.

Part 6: The Interpreter

This is where things leave the frontend. Surprisingly, from my experience, designing and implementing the frontend takes the bulk of the effort, and the backend work can be streamlined fairly easily. That may be because of the choices we made. In taking complete control of the solution, and offering maximum flexibility, up-front we made so many choices that led to handling all possibilities. Now we are left with something simple: the specific grammar rules we constructed, and a parsed and processed source that fits this structure. Although this structure is largely built up of generic data-types, we can be sure that this abstract syntax tree meets many rigid runtime constraints. So, one question becomes, what is the most effective way to operate on this data? Although this might not be the best solution, my straightforward answer was to use code generation from the programming language's grammar itself.

Each production is converted into a C function that is called with the production's leaf node from the abstract syntax tree. Basically, our parser has an extra step where it generates a C file with boilerplate code for each of our rules. We can call these stubs. Each of these production calls is dispatched from a table that associates production numbers (rule numbers) with the correct C function. These are called when a function decides to call InterpretNode on a child production.

Example:

/* 1. <program> -> <stmt list> */

int ReduceProgram(SYNTAX_TREE* node)

{

SYNTAX_TREE* stmt_list1 = node->children[0];

int error = 0;

error = InterpretNode(stmt_list1);

return error;

}This is the automatically generated production for our most basic grammar rule, the rule <program> ::= <stmt list>. Since this rule is fully recursive, there is really nothing for us to do. A better example that might show how the internal logic is supposed to work might be a statement or instruction that must do some work.

This grammar production for an expression rule tests equality.

/* 74. <comparison> -> <comparison> == <arithmetic> */

int ReduceComparisonA(SYNTAX_TREE* node)

{

SYNTAX_TREE* comparison1 = node->children[0];

SYNTAX_TREE* arithmetic1 = node->children[2];

VALUE comparison;

VALUE arithmetic;

int error = 0;

error = InterpretNode(comparison1);

comparison = gLastExpression;

if (error) return error;

error = InterpretNode(arithmetic1);

arithmetic = gLastExpression;

if (error) return error;

/* EQUAL */

gLastExpression = CompareEquality(comparison, arithmetic);

return error;

}We can see how our simple production rules are able to split the work that we are doing into manageable chunks. Our rule isn't concerned with the details of how a <comparison> or an <arithmetic> symbol is resolved into an expression or a VALUE in our backend. Instead, we can focus on the atomic operation of equality. Here we have made external the actual logic of CompareEquality to make our code more readable. Since we have a listing of 50 to 100 grammar productions, we want them to be as short as possible. This allows us to keep them in one place and ensure that they all are following the same conventions.

Working from the grammar directly poses its own limitations. Changing specific language features or simply tweaking the syntax may require re-laying out all of the work that has been done in crafting our interpreter. Some ways to lessen this burden might be to generate special constants and tokens based on the symbols in rules and use them to identify the rules. Or even better yet might be to directly name grammar rules. Additionally, it can be very helpful to create a set of functions or macros that allow for pulling out certain child data from a production, instead of getting stuck in a process of identifying array children and child node traits.

In any case, this is where the core of the language's work will be carried out. Evaluating the program will be dispatched by production number, and each production will handle its workload and process child productions as needed. The interpreter is aided by a virtual environment, or a runtime state and context, that it can use to track variables, procedures, function scopes, closures, and dynamic variables.

The main dispatch becomes something like this

/* reduce one node */

int InterpretNode(SYNTAX_TREE* node)

{

if (node == NULL || node->production == 0) {

printf("Null production.\n");

return 1;

}

line_error = node->line;

failed_production = node;

switch (node->production)

{

case 0x01: return ReduceProgram(node);

case 0x02: return ReduceStmtListA(node);

case 0x03: return ReduceStmtListB(node);

case 0x04: return ReduceIdentifierListA(node);

case 0x05: return ReduceIdentifierListB(node);

case 0x06: return ReduceOptEndlA(node);

case 0x07: return ReduceOptEndlB(node);

case 0x08: return ReduceStmtA(node);

case 0x09: return ReduceStmtB(node);

case 0x0A: return ReduceStmtC(node);

...

case 0x74: return ReduceBooleanA(node);

case 0x75: return ReduceBooleanB(node);

default:

printf("Unknown production %i.\n", node->production);

return 1;

}

}Here we allow the code generator to help us somewhat by creating the jump table we will use in identifying productions. This isn't strictly necessary. One choice we've made here was the ability to track errors on a production by production basis. If we replace this logic with statement by statement errors, we can move this error checking into our <stmt list> production. Then we could track our production functions with function pointers stored in the abstract syntax tree. The benefit this provides is eliminating one function call for every rule definition. This could be a large boon for performance. Instead, we won't occupy ourselves with performance right now. There are a number of ways we can optimize our code and logic to provide much better performance in the future.

The runtime itself is deceptively simple. In general, all of our computation is stored in a single global variable (a very poor design). This expression, gLastExpression, represents the value from the last operation or function call. Something like an addition operation will evaluate its first operand, store the result in a temporary value, evaluate the second operand, store the result in a temporary value, and then add the two results and store them in the gLastExpression register. Working in this fashion allows us to use return values for error codes, especially when not all productions return an expression, per se. The data we need from performing simple computation and our temporary variables are automatically stored on the stack. Our more complex storage requirements will be met by the heap.

We will continue to fill in the bodies of each of our productions. Operations like add, subtract and multiply are somewhat simple. All of our orders of operations were handled by the parser, so all we need to be concerned with is the actual arithmetic we are performing. This can be something like checking if we are dealing with numeric types, adding the numbers, if one or more of the operands are real numbers store the result in a floating-point variable, and if we have strings involved do something like string concatenation instead. All of this is implementation specific, really.

There are other productions we have that don't deal directly with expressions. And there are also productions that we are using for syntactic forms that don't necessarily make sense on their own.

Let's look at our grammar for function definitions, a certain kind of statement.

<function def> ::= function <identifier> <parameters> <endl> <stmt list> end

<parameters> ::= <epsilon>

<parameters> ::= ( )

<parameters> ::= (<param decl>)

<param decl> ::= <identifier>

<param decl> ::= <param decl>, <identifier>

A function definition statement has an identifier, the name of the function, an optional list of parameters or arguments, and a block of statements that represents the function body.

What we need to do with this information is create a record for this function in the current scope that we are in or our current function closure. This record needs information about the parameter names, the function body, and our current scope to be stored in this record, and it will be stored under the function name. We will get the list of parameter names by iterating through the <parameters> symbol, identifying its production number, and traversing its children. In this context, that would be node->children[2].

Our design goals stated that we wanted to use functions as first-class objects, so we need to store them in the same way that we store strings, integers, and floating-points. As we are working with values and storing them, we will create our own data type for variable storage, called a VALUE type. This will be a union of all of the possible types we can store. So, it will have a field identifying what the object's type is, and then it will have fields for possible integer, floating-point, string, function or dictionary values.

Integers and floating-point numbers can be stored directly in a VALUE. The other types need to be stored by reference. Strings will be allocated on the heap and then accessed as constant character pointers. Function objects, which store a sort of header of information, will also be stored on the heap, as well as dictionaries.

As we said, a function object needs to be aware of its parameter names, the body of statements it contains, and finally, the scope in which it is declared. Statements inside the body of the function will be able to access variables declared around the function, but not variables from the context that the function is called from, unless these two scope levels intersect. In this case, the Duck language will use lexical scope, rather than dynamic scope. Later, it will be important that we consider all of the ways that these overlapping scopes can interact when we build the garbage collector.

Outside of simple manipulation of expressions and working with more complex data types, we must also be concerned with some of the more complicated statements we are supporting. Although assignment seems like a simple task, we need to be concerned both with how we structure this in our programming language's grammar and also with how we implement it in our language's environment.

Consider the case where we allow assignment to variables from expressions or from other assignments:

<assignment> ::= <l-value> = <assignment>

<assignment> ::= <l-value> = <condition>

We must consider here what the definition of an l-value is. An l-value is the named variable on the left hand of an assignment statement. We will need a more complete definition to continue. An l-value might simply be the name of a global or local variable. Here the scope of a variable is determined by when it is first assigned and the scope of the executing code, as we have not implemented anything like declaring variables. An l-value might also be an index into an array or a dictionary property. In general, l-values can be used as references and references can be used to address l-values.

Let's see this defined in context-free statements.

<l-value> ::= <identifier>

<l-value> ::= ( <l-value> )

<l-value> ::= <reference> . <identifier>

<l-value> ::= <reference> [ <expr> ]

<reference> ::= <l-value>

<reference> ::= <reference> ( )

<reference> ::= <reference> ( <arguments> )

What this shows us is that we need to work carefully to identify which member variable we are referencing in assignment. What we should also consider is what may make up the right hand side of assignment.

The right hand form of assignment must be a <condition> or another <assignment> symbol. A <condition> is the highest order of expression. In fact, we have a rule stating that expressions reduce to conditions, <expr> ::= <condition>. The hierarchy then proceeds from <condition> symbols to <logic>, <comparison>, <arithmetic>, <term>, <factor>, and lastly the <final> non-terminal symbol. These are in order of increasing precedence in our order of operations and exist mainly to help the parser. Our definition of a <final> or final term is either a parenthesized expression, a Boolean, an integer, a float, a string, an object declaration/definition, or a reference, the last of which implies that a <final> may be an l-value.

So, when dealing with assignment, we have more strict rules on the left-hand side than the right-hand side. In evaluating an assignment expression, we want to start first with the right-hand side and hopefully return with a result value that we can store. When dereferencing things, we can operate as we have with other expression productions and determine a result and store it as the gLastExpression. For an identifier, we lookup a variable using the identifier name. For a reference, either as a dictionary or array, we first determine the value of the reference, as a value object, then use that object with our identifier to retrieve the target value. Our rules for reducing l-values will be different. At any given time, we will only need to track a single l-value. If it is being used on the right hand side then this comes before being dereferenced but after being identified. On the left-hand side, it is possible for an l-value to reduce to an index of a reference. In this case, after we have determined the value to store or assign, we will evaluate this reference and hold on to the object. We will then use it as the storing context. If there is no reference, the context is the current level of scope.

To elaborate more clearly, we will use a global register gLValueIdentifier when working with named l-values. In the case that we are indexing an array, as in the fourth rule, we will use a register called gLValueIndex. Finally, there are two cases for assignment: storing a value in a variable or storing a value in a dictionary. So we must track not only which of these we are dealing with, but also the given scope or dictionary to use for storage. So we will introduce two more registers, gLValueContext and gLValueDictionary. The main concern would then be to keep these all straight as we proceed.

Another complicated case might be the use of dictionaries in initialization or in statements. Arrays when initialized can be evaluated as a list and stored one by one. In the case of nested arrays, it is important to make sure the interpreter's internal registers aren't being overwritten. This is really a practical concern to our runtime. In general, array and dictionary initialization will behave as a series of assignments of evaluated expressions. Accessing and modifying dictionary elements will also be supported using our own data structures, which will be discussed further when considering the execution environment.

Finally, we must consider our control statements. One of the first structures we considered when setting out to design and build a language was the if statement, the else statement, the for loop, and the while loop. What we did not mention was else if statements but we will show how we can support those.

It's best in implementing control structures to approach things from a higher level. An if-statement can behave by first obtaining an expression, the conditional, from interpreting part of its syntax tree. The if-body can then be interpreted conditionally, if this expression is "true." We need to define our own rules for Boolean logic when coercing values from other types. Similarly, while loops will behave in the same way, except for repeatedly evaluating the condition, and optionally the loop body, until the looping terminates. For loops might be the most complex but involve similar logic and are mostly implementation defined.

In discussing the syntax for an 'else if' more than the procedures of how else branches will be executed, which should be on about the same difficulty as our other language elements, we will have to go back to the grammar.

One possible way of formalizing this in a context-free manner is the following.

<if> ::= if <condition> then <endl> <stmt list> <else if>

<else if> ::= else <endl> <stmt list> end

<else if> ::= else <if>

<else if> ::= end

Luckily for us, the way we use newlines and the phrases "then," "else," and "end" in our syntax gives us a clear definition as to how a sequence of if, else if, and else statements should be parsed, without ambiguity.

Pragmatically then, we will interpret the <else if> node only if the condition is false. In that case, that could lead to either a <stmt list> that is always executed, an <if> statement that is also executed, or an empty production.

That determines a large number of the ways we are set to handle all of the different kinds of statements and expressions in our language, but also leaves us with some loose ends in terms of how we will implement all of this. It would be daunting to start from scratch here, I know, so it's best to approach the construction of the interpreter after we already have a toolbox of resources available. This is also largely dependent on the language and tools we are using to fashion the interpreter. Using C with minimal libraries, we need to create a number of our own data types, including lists, trees, dictionaries, and hash tables.

Part 7: The Virtual Environment

First and foremost, we must have some idea of the data that we will be working with and manipulating in our language's runtime. As we have already decided, values that are used in a Duck program must be stored with information about their type because of its dynamic nature. We have also discovered that the built-in types for integers and floating-point numbers can be passed by value, stored in a VALUE structure, and that strings, functions, and dictionaries must be passed by reference, as pointers in a VALUE structure.

In evaluating and storing information at varying levels of scope, we need a way to access and assign variables that have names. In this case, the simplest case, we will use a list of VALUE structures paired with string identifiers and label this as a CONTEXT. A CONTEXT can have a parent, which represents a higher level of scope, and so we have a tree of identified variables. When accessing a variable, we will continue up this chain of parents until we identify the value we are looking for, starting with the local scope and continuing to the global scope.

The dictionary and array types will be stored differently. A dictionary will be accessed as a hash table. Values used as indices, whether they are strings, integers, floating points, or object references, will be first used as input to a hash function which will find a container, and then the given value will be stored or retrieved. This offers us better performance as it is closer to O(1) constant time. Additionally, we can use some sort of optimization like this on ordinary variable retrieval for increased performance.

An interesting case to consider is when a function is called. When this happens, anonymous expressions which are passed in as arguments are bound to named variables, the parameters, and a new scope is created, the function's closure. The parent of the function closure's context is the context or scope in which the function was declared. We determined this when we made the decision to use lexical scoping.

Aside from the definitions we have for values, contexts, functions, hash tables or dictionaries as data types, there may be some other information that we need to access and store. As function calls are made and returned, we might need access to that closure or scope level. So, we should keep a call stack of functions that are currently executing. This also helps us for debugging runtime errors, an issue that we haven't really discussed.

The Live Interpreter

One of the best ways to test and use our new programming language is with a live, interactive terminal. We call this the Read-Evaluate-Print-Loop or REPL. Implementing something like this won't be difficult for us, but it will take a few more additions or tweaks to the system we have already. Recall that our parser used a number of states to organize our program source into an abstract syntax tree when provided input from the lexer. Now remember that there were several ways for this process to fail. One of these failure cases was when the parser was looking for more input, usually for a shift operation. Well, instead of failing at this point, an interactive interpreter offers us the option of running a program in parts, and also allowing a terminal user to provide the program line-by-line.

In general, we can take an input line from the user, run it through the lexer, then the parser, and interpret it to change our virtual machine's state, and then print the result. However, sometimes a valid section of code can't fit on a single line, like function declarations in our case. Then we will need to keep requesting input until we have the whole thing. We should also recognize when we have encountered a syntax error and need to throw away this buffer.

Here is a simple program, written in Duck, that provides an interactive interpreter. It is included in the main program, to be executed when running the interpreter without any input.

/* Duck REPL ** Enter statements to be evaluated. */

duck.println("Duck Language REPL - type quit() to exit")

running = true

while running do

program = ""

typing = true

expr = 0

duck.println("Type expression or statements:")

while typing do

line = duck.prompt(" > ")

program = program + line + duck.newline

parsable = duck.parses(program)

if parsable == 1 then

typing = false

else if parsable == -1 then

duck.println("Syntax error.")

duck.print(duck.newline)

program = ""

end

loop

expr = eval(program)

if expr or Type(expr) != 'NIL' then

duck.print(">> ")

duck.println(expr)

end

duck.print(duck.newline)

loop

This is a great tool for accessing the language and increases its utility as it has already become a sort of pocket calculator to the programmer.

Part 8: The Library

No language is useful in a real or practical way without the ability for programs to provide input and output. For this to happen even in the simplest of scenarios, we need to start implementing a standard library. Beyond what is included with the language, it would also be nice if other programmers could contribute to what we have accomplished by developing their own third-party libraries, so we ought to orchestrate a way in which external code can be linked with our programming language.

The best way we can do this is first to expose useful functions to integrate code with our language and then to provide a way that native code can be called from inside our programs. One simple way to do this is to override our definition of a function object with additional information. By adding a field for an external function call, a function pointer, we can provide hooks to library functions and store them in the global namespace. Furthermore, with some simple manipulation, we can create our own namespace for a library by using a named scope.

The way that our library will interface with the Duck language is relatively simple. At start up, the language will bind libraries that are included in its distribution. During this phase, the library has the opportunity to create hooks for its common functions, data, and constant data. Functions are integrated by first providing a pointer to the procedure and then providing a list of the named parameters. As we allow for any type of object to be passed as variables, our external code will have to retrieve VALUE objects and handle them manually.

A function itself will take an integer argument count as its parameter and it will return an error code. Returning zero indicates that there was no serious error in executing the library call. The function is able to access values, both from its parameters and also the runtime scope using the GetRecord command, an internal instruction to the interpreter. The library function is able to return results via modifying the gLastExpression register.

Part 9: The Garbage Collector

With all of these concerns handled, to some degree or another, we need to consider our program, the interpreter, and its memory footprint. In first implementing the programming language's runtime, it makes sense to override the default allocators, malloc and free, with our own allocator and deallocator. This allows us to track our memory usage and free extraneous data when our environment exits.

This is the best way to provide memory management in the first stage of development, because all memory is automatically freed when the system shuts down. What it doesn't provide us, however, is any sort of guarantee that we will continue to have memory when running our program, because it may just continue to eat up dynamic objects and never return them.

There are a number of schemes we can use to track and free dynamic objects, most of which are termed "garbage collectors." We want to provide our programmers with automatic memory management, so this is an area we must explore. There are multiple ways of handling this and we will consider their pros and cons.

Naively, one of the best ways to free variables on demand might be reference counting. Given a dynamic object, such as an array, we know that when it is created it has 1 reference, which is whatever scope or temporary value it is in. If the value is discarded or our global register is overwritten, it has 0 references and should be freed. If it is assigned to a named variable, its number of references is increased, and if it is assigned to multiple named variables, it increases again. If the scope or context holding these references is destroyed, its reference count decreases, until finally, if the last reference to the object is lost, it should be destroyed or freed.

There are a number of advantages to reference counting as a garbage collection method. First of all, it does not require stopping execution to reclaim memory. This is something that happens automatically as objects come into and out of scope. It is also relatively easy to understand and should be simple to implement.

Reference counting as a form of garbage collection requires a careful watch on when objects are destroyed. If an object is destroyed, all of its elements must be checked to decrement references that they may hold to other objects. All of the possible places where references can be made, increased, or decreased have to be handled precisely, as if we lose count by one, then we will either leak memory or try to free the same memory twice. Additionally, there are certain types of circular references that may never be freed under this scheme.

Which leads us to the next form of garbage collection: the tracing garbage collector. What this method involves is, first holding a list of every dynamic value, every dynamic string, every context, every function, and every dictionary or hash table from the moment it is allocated. This doesn't have to be a list, it could be any data structure that allows us to find and locate elements and also iterate through each of them. What we will do is, occasionally as our program is running, we will stop execution. Then we will look at all of the variables that the currently running program has access to, including the entire call stack. This must include local variables, global variables, any object that references another variable, and any functions that can access a given context or closure when being executed. When everything that is still 'alive' is identified, we compare this with all of our allocations. Anything that we haven't identified is now 'dead' and can be removed from memory.

This method has a number of pros and cons, too. It requires stopping the program occasionally, known as a stop-the-world garbage collector, which can be a detriment to some applications. Additionally, it might take some more work upfront implementing, as it involves tracking a large number of objects and all of their interactions. However, once in place it is a very effective way to free memory that is able to find dead links including circular references. It's also very much behind the scenes, as long as allocations are being tracked.

The Duck programming language currently uses a tracing garbage collector. It is highly accurate and handles a number of issues like dead call stacks and parameter lists rather well. One concern would be to offer better integration with user libraries, which is definitely one area for improvement in the future. There are also a number of ways to go about improving its performance by using better data structures.

End Notes

Because of how we have arranged everything, it would be trivial for us to take this language and turn it into something else completely. With a few tweaks to our parser grammar, we could have a programming language with the exact same functionality that looks like C. Additionally, with some additions to the lexer, we might begin to enforce rules on indentation. Then our language would become like Python.

One of the great benefits to setting up our experiment this way is that it gives us complete flexibility. Earlier it was stated that dynamic languages are interpreted and static languages are compiled. This isn't always true. Furthermore, we can take a static language and relax the rules around type safety, essentially skipping over the step of type checking and passing that on as a runtime concern, and we could craft an interpreter around a familiar language that we know.

In terms of our parser generator's power, we are able to parse early-Java programs, stuff from version 1.0. This is because the language was originally designed to be an LR(1) grammar, or completely deterministic. Later features have changed this, like C and C++ which are also not strictly context free. These are challenges but they are not insurmountable and generally require a few extra stages or steps to be added to our lexing and parsing pipeline. Additions like a pre-processor and post-processor mainly would help us with this task.

So we can already see how we might make a language like Cscript, that can run C programs itself by executing them in an interpreter. This just shows how interesting programming language design can be, before even looking at practical applications.

In general though, we will begin to see the limitations of using an interpreter to execute all of our programs. The way we have designed our language, there's not much we can do here. One of the best things we could do would be to squeeze as much performance out of the backend as possible and provide our programmers with great tools and libraries to be productive.

Ultimately, if we want to go deeper than that, we will need to start looking at compiler techniques. Our language has completely dynamic types, meaning that if we are performing even simple operations, we need to determine what types we are working with. If we were going to begin to compile this code, we would still have a large amount of overhead there. Instead of an addition becoming a single op-code, it would involve a function call that would sort all of this information out for us. Although this might still be significantly faster, it represents a lot of work for us as language designers. As an interesting exercise, it might be fun trying to cross-compile our language to another dynamically-typed scripting language. This offers us a bit more portability by allowing our code to run in more places. As part of the Duck language design, one intention is to allow programs to run on Desktops and on the web. For that reason, I implemented the Duck interpreter in JavaScript. This is great in concept, however it doesn't achieve 100% performance. A great next step would be to implement our shared libraries in JavaScript and then offer a way to cross-compile programs.

Although this would be an interesting project, I'm sure that we are all wondering whether we can design our own static language now. One important step in a language's continuing improvement, and a step towards making it more independent, is the ability for it to become self-hosted. Our Duck language lacks the resources to write a Duck interpreter itself while still being useful in terms of performance. While this would certainly be possible, it would not be useful. Instead, we will have to start from square one for this project. Please see "Designing a Programming Language: II," the second part in this series, to see me discuss the ways we can design our own statically typed language and lay out the road map for us to write our own compiler.

Best of luck.

References

The legendary green and red dragon books, by Aho and Ullman and Aho, Sethi, and Ullman.

[1] "Principles of Compiler Design." Alfred Aho and Jeffrey Ullman.

[2] "Compilers: Principles, Techniques, and Tools." 1st Edition. Alfred Aho, Ravi Sethi, and Jeffrey Ullman.

[3] The Duck Programming Language Official Website

[4] The Duck Programming Language Parser Generator

[5] "Engineering a Compiler." 2nd Edition. Keith Cooper and Linda Torczon. Morgan Kaufmann 2011.